Marine contagious metastases

Watch out! If you are a researcher that would like to study marine contagious cancers, do not hesitate to contact me at albruzos@gmail.com!

What is it a contagious cancer?

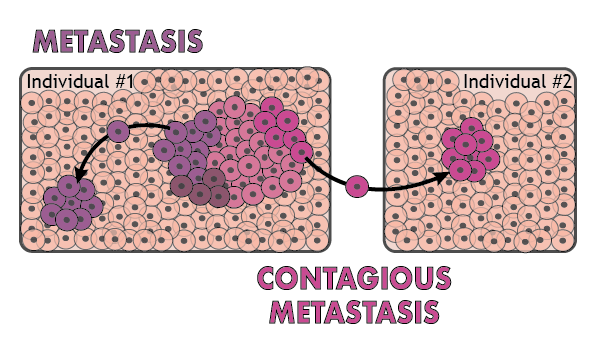

Cancer occurs when a single cell in the body acquires genetic changes that drive inappropriate cell proliferation. Once initiated, cancer evolves by natural selection, often producing cell lineages that spread through the host by a process called metastasis (Murchison EP, 2016). However, cancer does not normally spread beyond the host’s body.

A contagious cancer or clonal transmissible cancer is spread directly by the transfer of cells between individuals.

Are they caused by a virus or pathogen?

No. Some tumors are induced by infectious agents such as viruses, and though these agents can be contagious, each tumor still arises in the infected individual by transformation of somatic cells (Metzger MJ, 2015). In contagious cancer cases, a tumor cell itself naturally spreads among individuals as a transmissible cell line.

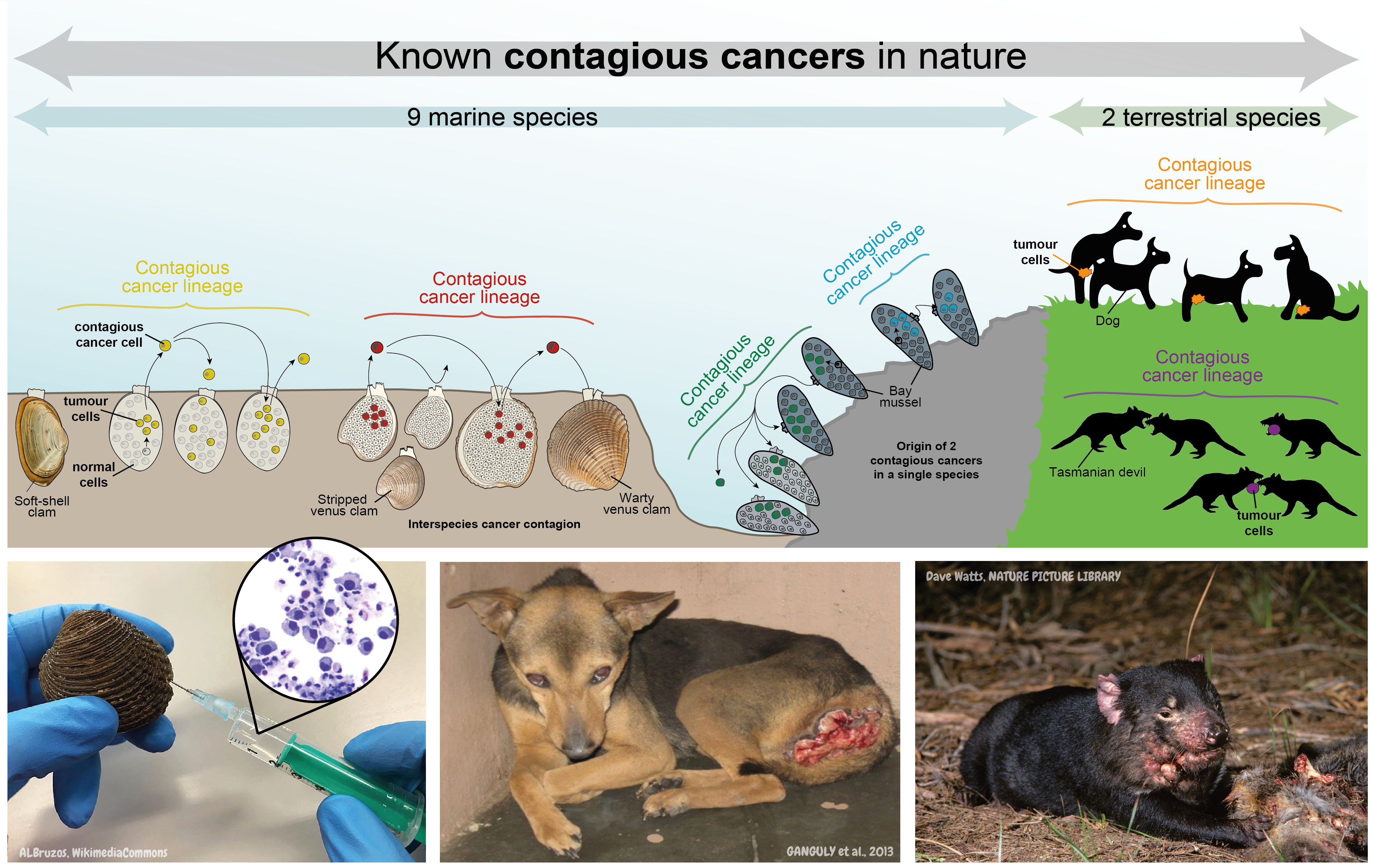

What cases have been reported in nature?

Contagious cancers are known to occur in dogs (CTVT), Tasmanian devils (DFTD), and several marine bivalves (BTN).

Want to know more?

- TED talk: Fighting a contagious cancer (Tasmanian devil)

- Video: 11,000-year-old living dog cancer reveals its secrets (dogs)

- Video: Genetic causes of contagious metastases buried in the sandbed (bivalves - cockles). (Spanish audio, English/French subtitles)

An ecological threat!

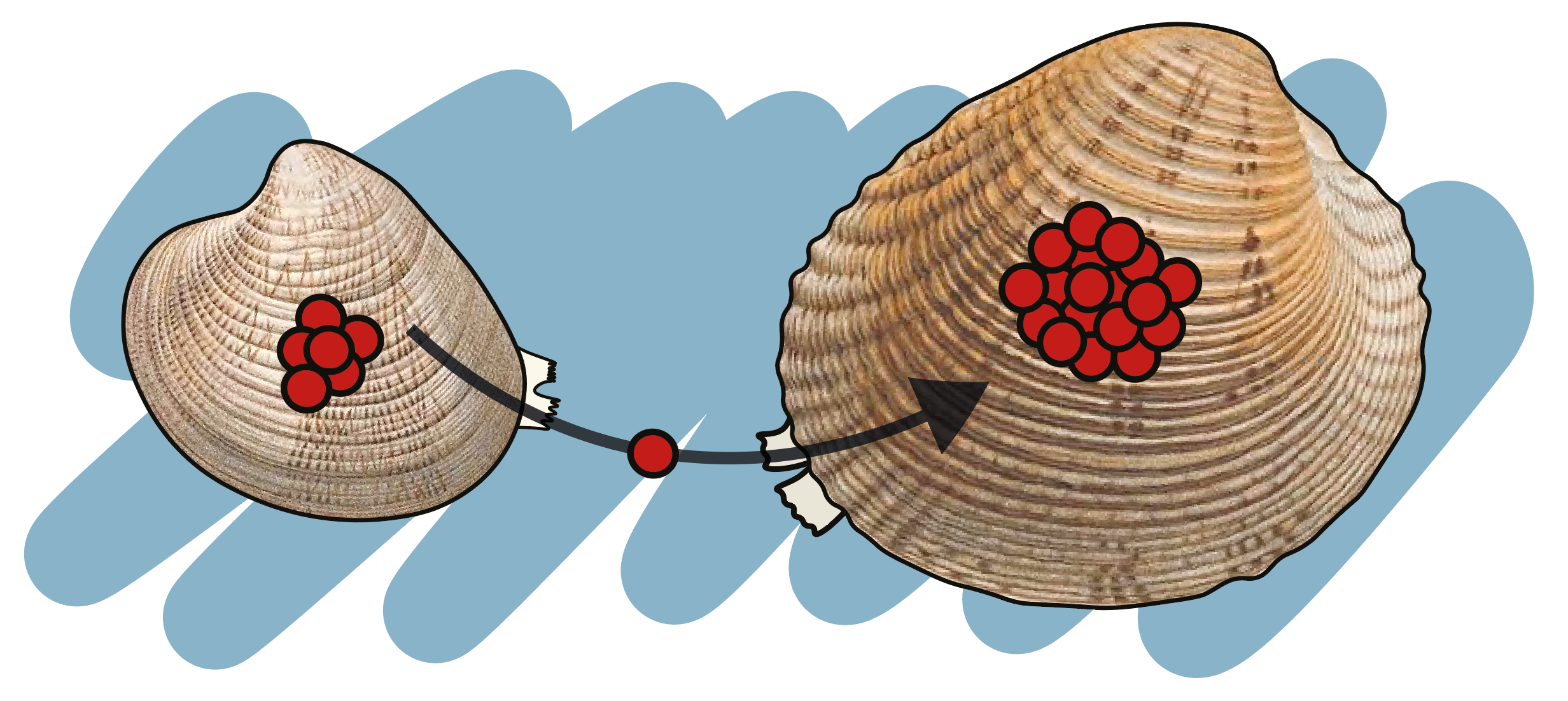

Some marine contagious cancers can even cross the species barrier! One of my first discoveries in the field of contagious cancers Life, 2022 was the case of cancer contagion between clam species in the Seas of Southern Europe: Video English version or Spanish version

What can bivalves teach us about cancer?

From humans to bivalves. Throughout my career, I have gained a robust and in-depth foundation for working on transmissible cancers through my extensive training in the field of human cancer genomics. For the past 8 years, I have worked at the forefront of cancer genomics, having participated in some of the latest and most important discoveries in the field, such as: (1) the identification of genomic instability caused by aberrant insertion by LINE-1 retrotransposons in several cancer types (Nat Genetics, 2020), (2) the identification of chromosomal instability caused by hepatitis B virus in hepatocellular carcinoma (Nat Comms, 2021), (3) the characterization of the cancer genome through an integrative analysis of 2,658 human genomes (Nature, 2020), and (4) the identification of BRAF fusion genes as a recurrent cause in congenital melanocytic naevi that usually leads to melanoma (JID, 2023).

My extensive training and research on the genetic processes involved in human cancers has provided a vigorous basis for my research on transmissible cancers, namely the discovery of a novel marine contagious cancer spreading among different clam species (Life, 2022), the development of a multiplex PCR assay for the detection of two cockle transmissible cancer lineages (preprint, 2023) and, the genomic characterization of two contagious cancers in cockles, including the mechanisms that allow cancer to persist, such as the horizontal transfer of mitochondrial DNA, similar to some human cancers, their extensive genome instability (e.g., complete genome duplication), and their ontogeny (Nat cancer, 2023).

My research bridges different fields: cancer research, evolution, and marine ecology. I found that the genetic mutations that shaped the evolution of a cell to become a contagious cancer cell were similar to those in human cancer, namely a duplication of the complete genome (Nat cancer, 2023). However, the level of chromosome instability in these contagious cancer cells is much higher than in human tumours suggesting that stable genomes aren’t necessary for the long-term survival of transmissible cancers. This is surprising, as human cancer cells cannot survive high levels of chromosomal instability, although moderate levels often make tumours more likely to metastasize and become resistant to treatment.

Furthermore, contagious cancers may be more common in marine environments than previously thought given that phylogenetically distinct groups of bivalves have developed contagious cancers independently, suggesting widespread occurrence. This insight is crucial for understanding a disease that in late stages leads to bivalve mortalities, especially given the current threats to ocean health. Marine bivalves are not only important for food and fisheries but also play critical roles in coastal ecosystems by stabilizing shorelines and filtering seawater.

My career goal is to lead a world-class research lab focused on gaining mechanistic insights into the molecular, cellular, and ecological processes involved in the evolution of marine cancer contagion.